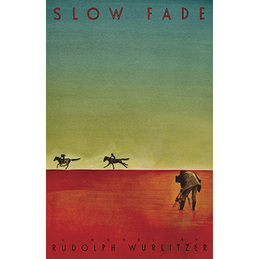

SLOW FADE BY RUDOLPH WURLITZER

Drag

City, 2011; Paperback, 194 pages

Will Oldham has released who knows how many albums in the sixteen or

so years since I first heard “For the Mekons et al.” on the “Hey Drag City”

compilation. On that track, he sounded like a candidate for “Dylan of His

Generation.” There was something intuitively right and representative about

the way he warbled an “executive branch in a nation of one, exercise your

power, to veto, veto, veto, be the man of the hour,” concluding “If we

drink, we still think, and we wake up in the morning, or we stay out all

night long: the righteous path is straight as an arrow.” The latter phrase’s

relevance wasn’t just in the words; the tone suggested an abstract manifesto,

like a campaign speech by a charismatic politician who hadn’t quite figured

out his platform but knew he was destined to lead.

Since then, Oldham’s fulfilled his early promise to create music that

stays alive, and that, as John Peel famously said about The Fall, is always

different, always the same. He’s constantly touring, releasing albums,

acting in films like “Old Joy,” and, most recently, lending his voice to

the audio version of Drag City’s re-release of Rudolph

Wurlitzer’s Slow Fade, a novel Knopf originally published in

1984, after which it never blipped on my literary radar until I heard about

Will’s involvement and subsequently acquired the paperback version Drag

City solidly designed and formatted so it looks, feels, and reads a lot

like one of those consistently excellent paperback re-releases from the

New York Review of Books.

Rudolph Wurlitzer, grandson of the guy who founded the famous organ

company, wrote a few novels I never heard of (his first, Nog, has

been called “one of the key stoned novels of the sixties”) and screenplays

for films I heard of but never saw (“Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid”)

or saw but barely remember (“Walker”). Drag City, a well-established independent

record company, infrequently publishes books, usually only by musicians

like John Fahey or the guys behind Royal Trux, Smog, or The Make Up. So,

of all the possible novels Drag City might republish, why Slow Fade?

Maybe it had something to do with the organ company, or with the fact

that Dylan did the soundtrack for “Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid” when

asked by his old friend, Rudy Wurlitzer, and Drag City wants to associate

itself with these associations? It’s worth scanning the Wikipedia

entry about Sam Peckinpah’s 1973 Western, since it suggests Slow

Fade’s relation to situations and circumstances of filming this movie,

but the novel stands on its own.

First off, the first chapter is a perfect example of the sort of opening

I imagine most readers are hoping to encounter. The prose is clear, the

scene is solidly set, there’s quick colorful talk among colorful characters.

Right away, the first chapter establishes a precedent of absolutely unpredictable

movement. Plot summary is available elsewhere online, but let’s just say

that things are immediately set up to head down a certain music-related

path before they swerve on horseback into the movies. The first chapter

is a more engagingly entertaining opening than any I’ve read in a long

time. If you read the first 6.5 pages, you’ll want to see how the following

188 or so pages proceed. That’s enough of a review right there: read the

first six or so pages and I bet you read the rest.

Otherwise, the rest seems concerned with running away from itself. Its

characters run from themselves, even as they try to “find themselves” in

what feels like a semi-satirical portrait of a very 1970s-style approach

to life, one that apparently involved a lot of spiritual journeying in

India? Stateside, there’s also a famous old director working on his nearly

fortieth film, his younger/hotter half-Eskimo wife, his son, and a derelict

musician from New York. The director is failing at every turn to complete

his film, it’s way over budget, the producer is threatening to pull the

plug. His final film, in fact, seems like it’ll actually be a documentary

of this failure, of his dissolution, of his turning away from everyone

in his life, his “slow fade” into solitude and death.

Despite thematic downers, this is a good-natured novel that’s for the

most part readable and clear. Characters are well-defined/differentiated

and alive thanks to plentiful dialogue and consistent description. It trots

the globe from New York to the American West to Mexico to India to Labrador

(and maybe a few other places). Throughout, characters are far from their

literal and spiritual homes. It’s a book in part about being “at the mercy

of whatever weirdness was coming down the road.” These weirdnesses often

seem to involve a self-induced freaking out; spiritual crises brought about

by what seems like self-sabotage; privileged ennui mixed with serious daddy

issues (“confronting death and separation and a few other essential questions

that I have no answers for”); consistent casual indulgence in drugs mixed

with a willingness to drift and effortlessly camouflage oneself to fit

where one temporarily winds up; and scraping the dregs of an artistic well

that once had overflowed (“. . . there had always been a sort of raw primitive

edge to his work, a kind of sentimental passion that every once in a while

would bring in gold from the box office. But all that was gone now.”)

Structurally, as mentioned, the story entertainingly refuses to settle

down, is always on the run, focused on three major characters as it sweeps

maybe too many minor players into its alternating-focus flow, especially

once it incorporates the italicized text of a screenplay by the director’s

son, a slant self-portrait based on his multi-year experience in India

and thereabouts, in part looking to find his lost sister who’d gone there

looking to find herself, which she’d lost thanks to her relationship with

her famous father. During these italicized story-within-the-story bits

I most often felt impatient, skipping ahead to see how many more pages

there were until things resumed in good old roman text, mostly because

the daughter/sister figure seemed insufficiently established in my readerly

imagination. Maybe an analogy can be drawn between what really happened

to the director’s son in India and what he writes about in his screenplay

and what really happened on the set of “Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid”

and what Wurlitzer depicts in Slow Fade? Maybe there’s a comment

there about how fodder becomes fiction, but I don’t have enough knowledge

of the stories behind the scenes of Peckinpah’s film. With it, the book

must be even more enjoyable.

One

review I saw referenced the so-called postmodern trickery of Pynchon,

Barthelme, and Barth, but I really wouldn’t put this book in that group.

This isn’t so much metafictional as metacinematic fiction. The comparison

also doesn’t quite work because the language straightforwardly serves the

story and its characters, plus there’s a commitment to dramatization not

so often found in the postmodern stuff of the ‘60s and ‘70s. Wurlitzer

at one point even has the director’s son point out that there’s been too

much exposition in his screenplay, which is sort of a shame for the novel

itself since Slow Fade excelled when it seemed more like a novel

than a screenplay (ie, more exposition than dramatization) and most dragged

when it followed the drift of its spiritually uprooted characters, particularly

the italicized screenplay scenes in India. After the absolutely engaging,

unpredictable opening, the rest seemed like a bit of a letdown, the consistent

movement never again as crisp and amusing as the change of scenery and

readerly expectation from page one to page ten. But thanks to clear attentive

prose, consistent dramatization, engaging characters that really seem to

breath the air of a wholly existing fictional world as they get drunk and

suffer hangovers, I was absolutely willing throughout to find out what

happens next, to see if another surprising turn would come, if there’d

be something more than a slow fade at the end, something that affirmed

the existence of the characters I followed for two or three days, so that

in the end the means to the novel’s end felt justified, and I felt satisfied

as a reader.

I didn’t feel totally satisfied, however, and thinking back on the book,

I think it may have intended to underscore the difficulty of achieving

contentment when lives are haphazardly, circumstantially, temporarily united,

lives already fundamentally freaked by unpredictable weirdnesses encountered

thus far. The best one can really hope for, therefore, is to dissolve like

the director does, alone in front of a fire when it’s cold outside and

you know it’ll get colder.

The righteous path might be straight as an arrow, but this novel is

more about the swerving path to dissolution for those who try and fail

to achieve a stable righteous self. Righteous readers are more lucky, however,

since it seems like Slow Fade might open up previously unknown territories

for the willing: “Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid” and the other films

of Sam Peckinpah, Rudolph Wurlitzer’s screenplays and novels (particularly

Nog), and, of course, the audio version of Slow Fade read

in part by Will Oldham.

*

Forever after at http://eyeshot.net/wurlitzer_slowfade.html