| Rejection letters transmitted by the

Eyeshot editor over the past dozen years have been selected from those

previously posted on this site, ordered, cleaned-up, addled with rejections

never before posted, and bound into book form by Barrelhouse

Books. It's availble now via the

Barrelhouse site.

Here's the first review.

This review

in Paste Magazine does a great job relating the history and context

of these rejections:

"These tiny, tight bursts of writing hummed with energy

that hopscotched among comical, cruel, warm, demented, high level and nitpicky.

Send him a piece of your soul on Microsoft Word, Klein seemed to believe,

and you deserved a piece of his soul right back. An amazing little act

of generosity, considering the number of terrible pieces of writing out

there. (Klein estimates that he has tapped out more than a thousand original

rejections.)"

Here's the Goodreads

page for it. Here are my

mom's thoughts.

Get it here

directly from the publisher. Or from Amazon

or Powell's.

Barrelhouse editor Mike Ingram asked the author (me) some questions

and I answered like this:

1. So, this book started with actual rejection letters you sent to

writers as the editor of eyeshot.net. What drove you to send people such

detailed responses to their work? That's certainly not the norm for editors,

as any writer knows.

One should always seek to astonish strangers, especially on the internet,

especially if these strangers are writers who've submitted to a crappily

formatted site with questionable content. As a comedic medium, the e-mailed

response from a literary editor is -- and certainly was almost 15 years

ago (August 1999) when I started the site -- totally ripe for exploitation.

Expectations are limited to a staid thank you and a statement of regret

that carries the burden of decline/rejection. So there's that -- it didn't

seem done at the time so it seemed like something to do -- plus I had had

a great interaction with Jill Adams and her husband at the Barcelona Review

in 1997/1998 when they worked with me on a story I'd submitted involving

a Black Sabbath cover band. The BR's designer grew up in Birmingham with

Black Sabbath and dug the story -- they also translated it into Spanish

and it was my first publication. So that interaction across the Atlantic

but occurring so quickly thanks to e-mail inspired me to try to connect

with submitters, even if I did so in less mature ways than the kind people

at the Barcelona Review. And lastly by the time I started Eyeshot I'd received

a few dozen form rejections for my own writing and so as an editor I wanted

to treat writers how I wanted to be treated as a writer. I wanted to know

why and I wanted to be entertained a little and I wanted not to wait for

more than a week, if possible no longer than a day.

2. Early on, those rejections must have taken submitters by surprise.

Were people grateful for the advice? Were they pissed? This was happening

over email, so I have to imagine you got some responses.

If someone responded, I responded, and if they responded to my response,

I responded again. I never deleted someone's e-mail and moved on if they

took offense or started insulting me. It's happened sometimes -- it happened

this past weekend in fact -- but I always respond and either mess with

them some more or smooth things over if they seem sort of crazy. A few

years ago someone really started insulting me in response to a comparatively

kind, helpful rejection, so I asked for his number and called him and yelled

at him for 15 minutes and he apologized and told me about his mental health

issues and ultimately said he'd buy me a beer next time I was in Brooklyn.

But generally, early on, I was trying in part to produce irregular content

for the site by engaging rejected writers who responded in one way or another.

Here's an example from April 2000: http://eyeshot.net/rejection1.html --

it's with Carlton Mellick III, who has gone on to found the semi-popular

subgenre of Bizarro Lit. What starts out generally antagonist ends in handshakes

and hugs.

3. You're also a writer, and like any writer you've received your

share of rejections. Are there any that stand out as particularly helpful

or particularly unhelpful?

The best rejection I ever received was from the Paris Review. I had

submitted something involving basketball hoops in suburban NJ -- it was

sort of a photo essay. This was probably in 1997. I received their little

square of a rejection note, but someone had drawn in blue crayon a backboard

and hoop and a basketball, which had clearly been shot from very close

to the basket and missed the hoop by a lot. I also received a helpful,

handwritten rejection from someone at the Chicago Review in 1997 that I

didn't really pay much attention to back then but I now appreciate. Nearly

all rejections I've received in the modern era have been form rejections,

or form rejections lightly modified to seem personalized.

4. This project, on some level, is like a purposefully over-the-top

response to the minimalism of most literary journals' standard, impersonal

rejection notes. Was that something you were thinking about consciously?

Were you bothered by those form rejections?

Yeah, in the days before Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, and even MySpace,

and Friendster before that, and even blogger platforms before that, I wanted

some more interaction with writers. I didn't know any writers at all in

1999. Even when I moved to Brooklyn in 2000, I really didn't know any writers.

It's hard to imagine now. So it was more about connecting with folks. But

I was aware that form rejections were slow to arrive and totally lacking

in telling people what's what. I wasn't bothered so much as I figured they

presented an opportunity I could take advantage of to differentiate the

site if I spent a little time and responded with my thoughts about the

submission, recognizing that I'd been out late the night before etc and

my reading of the submission was influenced by my emotional/psychological/physical

state and general environment, while also sometimes trying to confound

the submitter and entertain myself, all the while creating unique content

to post on the site that people tended to like.

5. When responding to people's work, do you ever worry about being

wrong? As an editor, I worry about that sometimes. What if I'm steering

someone in the wrong direction? What if I just didn't read their story

carefully enough?

Frank Conroy, the director of the Iowa Writers' Workshop when I was

there, would say "I reserve the right to be wrong." I love that phrase.

I also remember stoned conversations during my freshman year in college

about subjectivity. I'm never worried about being wrong because my response

to a submission, even if I skim the story and totally misread it, cannot

be "wrong" since there isn't a "right." (It also helps that I've always

edited the site solo, so I don't have to confer with other editors and

can steer the site in any direction at any time.) Criticism is always about

the critic's preferences. In workshops, each student only has a story "up"

a few times each semester because it's not about receiving helpful criticism

but delivering it week after week until students recognize patterns in

their responses that delineate their literary preferences. Also, unless

I accept a story, I've rarely read submissions anywhere near "carefully

enough." I tend to scan the literary DNA, recognize that it's not a match

for Eyeshot, initiate skimming activities, find a few things to write about,

and release the hounds.

6. At what point did you start thinking about collecting all these

letters into a book? And what was the process of selection? How did you

pare down years' of rejections into a collection?

Since 2002 I've posted batches or volumes of rejections on Eyeshot --

maybe a dozen in all. So the ones worth showing were selected long ago.

I copied and pasted them into Word in 2009 or so. Every once in a while

I worked on sequencing them. Added new ones as I wrote them in recent years.

And then when Barrelhouse greenlighted the publication, I worked with fiction

editor and friend from Iowa/Philly, Mike Ingram, to cut some of the weaker

or repetitive ones, tighten the language some, and shape things so if read

straight through there'd be more of a progression/maturation apparent.

7. Okay, last question. In the book, you reject several writers for

failing to adhere to eyeshot.net's rule of no dentist stories. What's your

problem with dentists?

That's just sort of a running joke in the book -- I started noticing

that I was receiving lots of stories that took place in dentist offices.

At most I figured it had something to do with cultural or aesthetic conformity.

Criticizing someone's writing is more like the orthodontist than the dentist,

I guess, trying to wrangle weird snaggle-toothedness to acceptable straightness,

but that's maybe an interpretative stretch. Mainly, I just started noticing

this disturbing trend, indicative of an apparently widespread deficit in

the writing population's imagination, so I added it to the submission guidelines

("NO DENTIST STORIES"), which of course meant I started receiving more

dentist stories, which is karmic punishment for making a big deal out of

something not so sinful after all.

*

This collection of rejection letters may appeal to:

-

Humor enthusiasts who leave smart/funny books atop their toilets to peruse

during single-sitting reading sessions and/or to impress house guests.

-

Creative-writing teachers looking to jazz up their syllabus with offbeat

writing advice that'll surely at least lead to spirited classroom discussion.

-

Fans of slant autobiographies (gifted/generous readers may discern a warped

portrait of the editor's life as he moves from Brooklyn (Greenpoint) to

the Iowa Writers' Workshop (Iowa City) to Philadephia (Cheesesteak Gardens),

maturing as human being and editor along the way).

-

Heavy users of Goodreads

looking for something quick and easy to review/rate and thereby accelerate

progress toward their 2014 reading goal.

-

Platonists (the rejection letters outline an ideal in the editor's mind

-- and we're pretty sure Plato once had something to say about the space

between the ideal and the real).

-

Former submittors interested in seeing if rejections they received made

the cut.

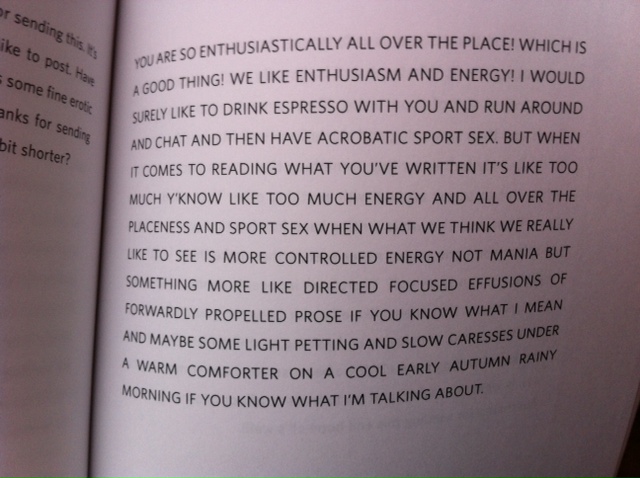

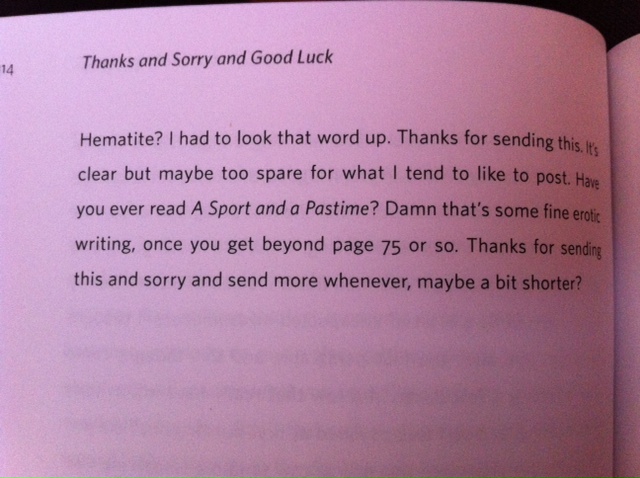

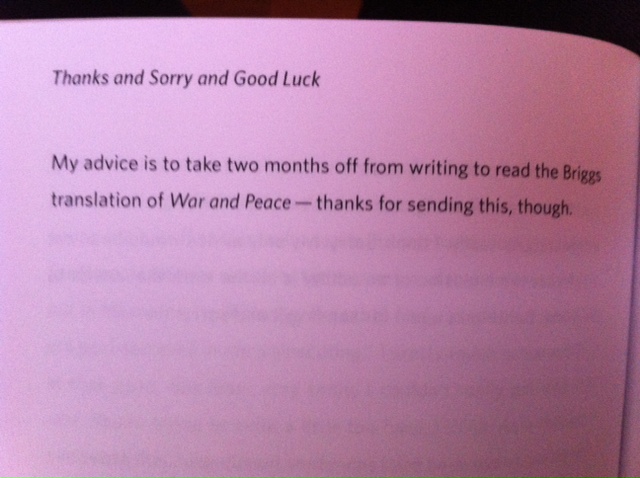

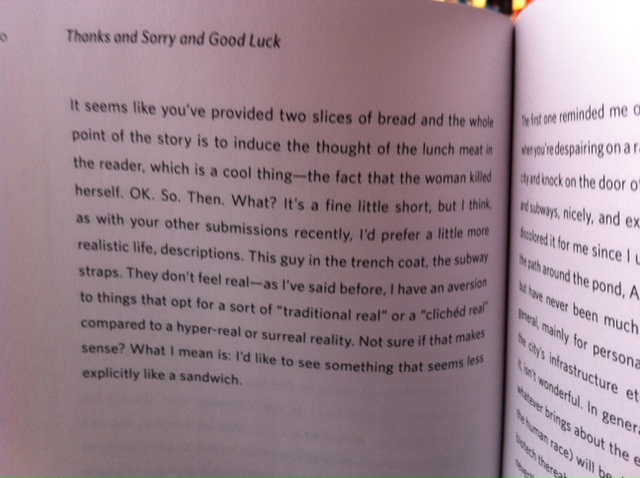

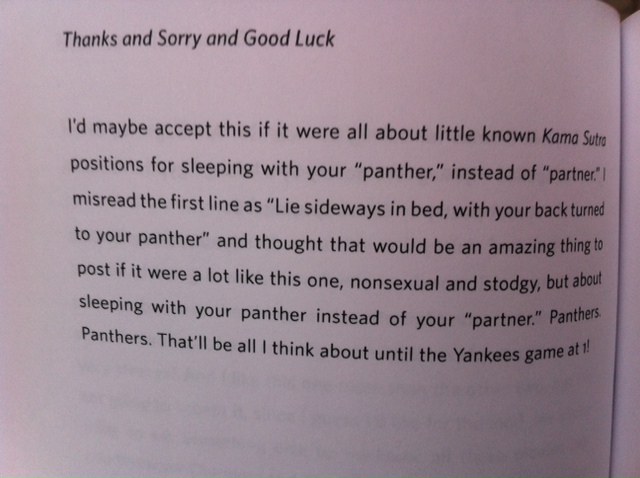

Very few semi-blurry photographic selections from

the 224-page book appear below (scroll all the way down and you'll see

four nice blurbs)

Four nice blurbs

Somewhere on the brutal truth continuum between Bill Hicks and Mussolini,

Lee Klein's rejection letters are mini-masterpieces of literary criticism

disguised as no-thank-yous from Writer's Hell. And yet, in each, a little

lesson; a steadfast faith that says "I took the time to read what you created

and this is exactly what I thought." They should be passing these things

out under the pillows at MFA camp; we'd all be better off.

-- Blake Butler, author of There Is No Year and Sky

Saw

To “decide” is to “cut,” and Lee Klein in the highly honed collection of

rejections, Thanks and Sorry and Good Luck, wields a drawer full

of gleaming cutlery, edgy edged instruments of decision. Surely, he holds

his pen like a surgeon holds the scalpel. These serrated graphs of glee

and screed are incisive incisions—katana, rattled sabers, sharp-tongued

stilettos of the split-lipped kiss-off.

-- Michael Martone, Author of Michael Martone and Four

for a Quarter

Sometimes writers who succeed against the odds brag about the number of

rejections they've accumulated. A rejection from Eyeshot's Lee Klein is

a whole different badge of honor. Like a letter from a serial killer on

death row, your Tea Party inlaws, or the Pope, they're suitable for framing

and brilliantly repugnant. I kind of want to send him a really shitty story

just so I can get one of these in return.

-- Ryan Boudinot, author of Blueprints of the Afterlife

Lee Klein made me cry. He was the only editor ever to make me. This was

back in 2002. I wish I still had the email. I remember it going something

like, “whenever you have the instinct to write a line like that, delete

it immediately, without prejudice.” I hated him for a while. I pictured

him looking like the guy in that 90’s movie Heavy (the one with Liv Tyler),

except housebound and with no redeemable qualities. Then, somewhere around

2004, I met him “IRL” and he was soft-spoken and sweet. It was harder to

hate him after that. Reading all of these rejection letters here in this

book made me finally fall a little in love with him, I think. I think if

I had had access to (and disassociation from) these letters then, I might

have fallen in love with him then. This is the funniest book I have

read in a long time. It is also the smartest. I feel confused now, like

I’m unsure whether to love or hate Lee Klein. But both of us are married

now so it doesn’t really matter.

-- Elizabeth Ellen, author of Fast Machine

ORDER

THE BOOK, IF YOU'D LIKE, VIA THIS LINK

|