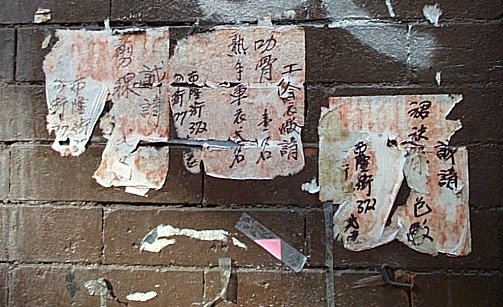

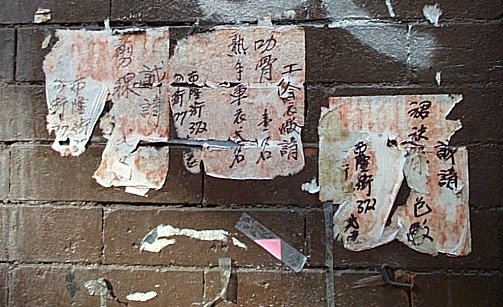

Translation:

372 West Celebration Street. The labor organization must collapse.

Please use your bones, all together, hand by hand. Send your names by car.

Sam and Mustapha were sprawling on the bamboo mats among the brittle baby toys, proudly nursing their bruises and wondering if Sam's nuclear family would ever get out of bed, when Dean Rong, in tow of the post graduate party informant, came to the door with an ultimatum from "the leaders," whoever, wherever they were."The leaders consider what you have done to be an extremely provocative act," Rong said.

Sam assumed that the trembling old man was referring to the previous night's provocative act. Around midnight, he and Mustapha (minus Sam's wife and baby, who had stayed home bathing because there was hot water) tried to get the thousands of kids to bring down the giant epoxy-resin Mao in Hong Qi Square.

"Go home and go back to bed," an underclassman had said in perfect English, sounding almost bored. "This is none of your business."

The police, always the most efficient and clever arm of this state, had sprayed water all over the place a few hours earlier and everybody was covered with bruises from contact with the perfect sheet of ice. The millions of spit gobs had resembled wads of cotton batting suspended centimeters deep in crystal. But to hear Mustapha tell it now, there had been brawls and mean fascists had kicked him in the pants.

Sam and Mustapha had needed entire bottles of baiju to stay warm. Their empties had bounced off the Great Helmsman's rubbery knees like ping pong balls, shattering somewhere among the crowd, the only bottles to break in any demonstration in the country that night. The response had been disappointing. The students were ten to fifteen years younger than the two foreigners, but were displaying very little Confucian elder brother respect.

"We're not vandals. We're not beatniks. This is not America. We're marching to the mayor's compound to make specific demands concerning local politics which you can know nothing about. Go back to your foreign expert buildings and take your Uighur narcotics. We need no American aid tonight."

"You piece of Tibetan duck shit," snarled Mustapha in Chinese, "do I look American to you?" And he informed them of his true nationality.

"Oh? And exactly where is that?" asked one large northern type at the front of the crowd. "Can you show us on a map?"

Whenever Mustapha began spitting out his native tongue and snapping his black and white shawl around like a bath towel, it was time to get him away from strangers--not an easy job in this country. Sometimes talking to him soothingly worked, sometimes only Sam's superior weight would do.

Last night Mustapha had allowed himself to be more or less arranged on the handlebars of Sam's black bicycle, and they'd spent the rest of the evening trying not to disrupt the baby's feeding schedule.

And now, this morning, as he faced Dean Rong and the post-graduate party spy in the corridor, questions began to congeal halfheartedly in Sam's head.

How could "the leaders" have responded so quickly to a provocative act performed less than six hours ago? Normally at least two days of political study meetings were necessary for a formal censure of a foreign expert. And why send the chairman of the foreign languages department to scold him? Surely inciting-to-riot rated a visit from at least a minor party official.

"Such a topic would never have been allowed--" Rong was saying.

At this moment Sam wasn't going to try to sort out Rong's strange Alzheimer babble about topics. He only knew that there was a more or less venerable Chinaman standing at his vestibule; and anyone who has skimmed the appendix in the cheapest five-and-dime Chinese phrase book knows that a warm welcome, tea and all, is valued above almost everything else in this country.

But Sam had no way of predicting how Rong would mix with his friend. Mustapha had already condemned him sight-unseen as a pseudo intellectual for having mastered English, French, Japanese, as well as his own native dialect and Pu Tong Hua, but not Arabic. Mustapha might easily call him the sallow residue of a noble race before the jasmine blooms had sunk to the bottom of the single university-issue porcelain teacup the baby hadn't yet smashed.

Mustapha loved Sam with a broken-hearted passion, precisely because his people had vowed to slaughter Sam's people one by one if necessary. (Until they'd met, Sam had never really thought of himself as having "people" beyond Polly and the baby.) Mustapha brought to Sam alone his waking nightmare/memories, for all his foreign classmates at the medical university across town had their own third-world horror stories and couldn't bear to hear more--Mibi, the Ugandan pharmacology major, for example, from whose lower torso entire sirloins had been carefully sliced

That left Sam to hear Mustapha's recitals over and over again: mother and brothers, entire village rocketed straight up into the sky before his nine year-old eyes; passportless sojourns in nations that officially welcomed his kind but treated them like vermin; foolishly distinguishing himself in the makeshift middle school instead of slouching and pimping in the alleys with his refugee cousins, and so, winding up in this filthy hell, studying gynecology on the soft Chinese currency that was extended to his people in the same supercilious spirit that Mormon aid is extended to Tongans; six years of assembly-line abortions, twenty or thirty a day, on suburbanite Chinese women who'd been deflowered too early in life, their vulvas deformed by forced entries; and, as though for variety's sake, the occasional hush-hush sex change operations on cadres' hysterical sodomite sons to forestall threatened Hong Kong escape attempts.

Sam and Mustapha had met on the night Reagan bombed the baby hospital in Tripoli, over a game of eight-ball in the art deco Renmin Hotel. Sam had refused to serve as representative of the American people at an afternoon disturbance outside the U.S. Consulate. (Afternoons were his turn to take care of the baby--he preferred afternoons because her bowels tended to move for Mommy in the mornings.) And so Mustapha had followed him out onto the street and offered to retroactively abort him with a pitiful Shanghai-brand scalpel.

Sam had laid the pretty little Philistine down on the cobbles and sat on him in a reverse David and Goliath scene, and was preparing to scream the customary disclaimers of Reaganite sympathies down into his face, when they'd both looked up and noticed the crowd of nearly a thousand that had gathered in less than thirty seconds. The natives were staring as with a single pair of slanted eyes at two individuals of the same species of sick, hairy, big-nosed zoo animal. And solidarity had instinctively risen in two alien breasts, made them pals, transformed Sam into the full-time manager of Mustapha's homicidal raptures.

In China, gossip is the main product of the workers and their state, the object and result of whatever diligence they display. Nosiness is the party's low-budget K.G.B. and F.B.I. rolled into one. Even a nationally venerated scholar like Dean Rong could be relied upon to care about the behavior of a desert neurotic two generations his junior--unless he had his own neurotic behavior to indulge in. In Rong's case, this morning, it was one of his own compulsive spiels that made him fail to notice Mustapha's scoffing presence on the other side of the door.

"We are colleagues and good friends," Rong was saying. "You know I suffered a lot in the ten years' chaos. They made big-character posters about me, placed me under house arrest and burned all my poems. They made me write self-criticisms for one year. You are a good man, and I am sure you will understand that you place me again in a difficult situation. I will be criticized severely for not keeping watch over my foreigners."

He glanced and trembled at the party suck who had obviously dragged him here, and he continued. "I give you my solemn word as a fellow scholar and teacher that there will be no persecutions. I've always dealt honestly with you in all our work together, and--"

Mustapha, who had been eavesdropping, shouted from within the apartment, "Tell him he must fuck his mother! In Chinese, cáo ni de ma! Or, wait, is it câo, employing the falling-rising tone? Sammy, where is your Hasner's?"

Sam turned away from Rong, who seemed to be thinking what it would be like to carry out the disembodied request. "Come on, Moosie," Sam said, as quietly as possible. "I'm sure fuck your mother's going to be in Hasner's."

"Sammy, is it proper for you, as a father, to say such dirty things in front of a child?"

The baby, awake now, began trying out the Mandarin fuck-word for herself. After making sure Rong had heard the baby's tiny guttural câo's echoing from the sleeping alcove (she seemed to prefer the falling-rising tone), Sam said, "Forgive me, but I must attend to the child." He shut the door in the leaders' mysterious envoys' puzzled faces--but not before Rong could shout out "--and so I must ask you to give me those examination papers right now, this instant!"

Examination? What examination? Oh yeah, two weeks ago already. Sam had not bothered to glance at them. Now the topic came back to him, along with the string of loaded questions with which he'd filled the glaring, primitive slate chalkboard. The retroactively forbidden exam topic:

Write on the new student democracy movement and its potential impact on your motherland's sagging modernization drive. Take into consideration the following questions:

1. Were big-character posters the workers' last means of self expression?

2. Should democracy be the Fifth Modernization, as certain of our undergraduate comrades who now rot in solitary confinement have suggested?

3. Is that "factory worker" they arrested last night really an itinerant Taiwanese spy with no visible means of support? Is he really intent upon corrupting China's golden youth? Or is he just some poor stooge they pulled at random off the street? Why was his face all puffy and caked with make-up on TV last night? Do you figure your fat leaders tortured him a smidge before he signed that confession?

You may use neither your Hasner's nor any other sources. Write for exactly two hours. At the end of that time, when I say "stop," put down your pencils immediately or flunk. Eyes on your own paper. No crib sheets. No leaving for the toilet. No talking.

It had seemed like a pretty good exam topic at the time. This was supposed to be a course in modern British and American novels, and Sam figured there might be a modern American novel in it somewhere.

Mostly out of curiosity, just to see if it would actually be possible to locate the papers, Sam began to poke among the refuse that cluttered the apartment. He now realized that he hadn't only forgotten about the exam; he'd also forgotten the students' names. Their maddeningly similar names, once so diligently memorized, had passed into oblivion.

He did seem to recall that one boy was nicknamed Trigger. Somehow that was a name Sam couldn't get out of his mind. He wondered if it was in honor of Roy Roger's famous horse, carrying the obvious sexual connotations. There were even more obvious Chinese sexual connotations: pao ma meant riding the horse and also jacking off. Or, perhaps it signified hair trigger, in the sense of premature ejaculation (zao xie in the local street dialect), a dysfunction legendary among the local intelligentsia. In any case, Sam knew he had a Trigger in the class, and his conscious mind no longer had an individual to associate with the name--but his unconscious mind kept sending up insistent, blurry images of an oval face.

Sam had started a model teacher. San Mu Lao Shi, the walking encyclopedia, the post-graduates had called him, and invited him to the reading room to talk. The first semester everybody, Sam as well as the students, had done beautifully on Orwell's 1984. Brave, dangerous things had been said out loud, right in class: a non-revisionist history of the party is impossible to get in China, but, in Hong Kong and America, books as true as Emmanuel Goldstein's are openly distributed; the insidious processes of Newspeak can be recognized in Mao's attempts to "de feudalize" Chinese characters, etc.

Sometimes Sam would get nervous and make discreet warning nods in the direction of the party informant (his head always down, seeing nothing, hearing everything, taking copious notes in the back of the grimy classroom); but the students would laugh and loudly proclaim with one voice, "In China, animals and English students are free!"

In the halls, in the dorms, in the nightmarish restrooms,signs suddenly appeared in English, Chinese, Japanese, even Russian:

WAR IS PEACE

FREEDOM IS SLAVERY

IGNORANCE IS STRENGTH

Then one day the pregnant pinto cat in the cafeteria was no longer pregnant, but no kittens were in sight--just four particularly smug and plump rats lounging in a melted patch of earth out back, an omen.

The students' persuasive essays began to de-politicize and sink to innocuous topics like child-rearing, and to be accepted for publication by the op-ed folks at China Daily, where they'd formerly been rejected with indignation.

Then the class switched, as the syllabus had given ample warning it would, from twentieth-century dystopias to contemporary novels in verse (a bibliographically manageable area of study, Sam assured them). Their pirated offsets of the decadent bourgeois Pale Fire turned out blurry, and the class lost its aim, flopped. No voices but Sam's drone were heard any longer. The party suck (Trigger?) felt the time ripe to move closer to the front of the class.

But the shreds of the 1984 signs still flapped from some of the walls; and it had been, Sam now recalled, mainly to win back the affection of his students that he'd resorted to the pedagogical hooliganism of that exam topic which was causing Rong to twitch so miserably among the barrels of barely preserved cabbages in the black passageway.

"What do you suppose they'll do?" Sam heard himself asking nobody in particular, in a slightly wavering voice. Mustapha held his arms high in the air and said, "Foreign expert expelled from the People's Republic. Interviews on Voice of America. Book contracts. Hope to stinking Jesus the reactionary pigs will send you home." Then he added, gleefully, "The leaders are probably just now hearing about what we did--"

"Failed to do," said Sam.

"--last night"

"A relatively minor disturbance," said Sam, trying not to sound nervous.

"No thanks to us." said Mustapha.

"Curricular subversion piled on top of extracurricular provocation," moaned Sam. "I wonder how they'll react. I've never seen the Chinese patience pushed to the limit."

"I have," said Mustapha. "At bicycle wrecks. They always have the traditional Confucian conference, instead of appealing to something so barbaric as the law. And teeth bounce all over the pavement during these conferences."

Polly woke up and rolled over. Sam looked into her eyes. She was the rational half of this marriage, and she looked a bit worried.

Sam had evidently become an academic right down to the walls of his arteries. He barely listened to the alarmist insinuations of his guest because he was too busy worrying about his reputation. He didn't want his good name to become politically tainted in the Middle Kingdom and lose the glory which the otherwise cynical Chinese fatuously attached to the Ph.D. that followed it. He couldn't afford to be dissociated from the resume-swelling projects over which he and Rong had been cackling and salivating in the good, golden pre-democracy days of Sam's tenure this side of the Pacific. In spite of their differences at the moment, Rong and Sam shared an almost infinite capacity for typing, self-aggrandizement, and neglect of the classroom.

Now, if he failed to deliver up the exam papers (and, along with them, in effect, the students themselves), Sam would have to retract and trim back down to a page and a half the hundreds of vitae he'd sent to every continent in the world. There would go any chance of escape from China, and any justification for having schlepped Polly to China in the first place.

Mustapha slid a little closer to Sam on the bamboo mat. With a terrible appetite, he ascended to a new plateau of communion. He expressed dark, paranoid thoughts.

"The leaders here are famous, even in China, for Maoist extremism," said Mustapha. "This city was the last bastion of the Cultural Revolution. If you don't believe this, ask the old man." He twitched his squatty body in mockery of Rong. Laughter almost adulterated his strange passion for an instant.

"Even now," said Mustapha, "during anti-crime campaigns, when most places save their bullets for murderers and rapists and embezzlers of over five figures, here they liquidate boys for saying lascivious things to girls. And what about your predecessor, Sammy? The party line is that he gradually poisoned himself to death with rice spirits in this flat, perhaps on this very mat. But have you ever asked yourself why they didn't just dismiss him from work and send him back to America for his death?"

Polly sat up and said, "In socialist countries they have no apparatus for firing people."

"Did you know he was distributing photocopies of letters smuggled from the democracy-and-freedom pupils' cells?" asked Mustapha. "You know, I never saw him touch baijiu, only beer. If he had taken as much baijiu as they say, one match lit in his vicinity would have been enough to cremate him. But I did see his face swell and I saw his character and his mind turning to rice porridge. How convenient that they burn people here, along with their telltale connective tissues and organs."

Mustapha leaned his head back and began to declaim at the concrete ceiling. "Mibi says our leaders caused the pharmacology majors secretly to cook vats of synthetic hallucinogens in the lab in those days--what the Public Security Bureau calls tougaigu dian, electricity for the top of your head."

"Perhaps better rendered skull lightning," said Polly.

"They know how to paint doorknobs and bicycle handlebars with that poison, and it can pass through the flesh of your hand. Just ask your former Minister of Security, G. Gordon Libby, whose fruit company has enslaved countless thousands of peasants in South and Central America."

Mustapha began to elaborate further on the seamy side of American foreign policy, but the baby stopped him with a scornful fart noise from between her boneless gyms. Bored, she eased herself off the bed to play in a pile of toys and papers.

"If you go crazy and die they will try to take the baby away from Polly because she is only a woman."

Polly said, "Never. They have no concept of social services."

Sam wanted to absorb the tiny round girl into his matted chest hair. He forgot about publishing and began to think about perishing. How could Polly manage with him a pile of ashes? And the Chinese liberating his daughter was out of the question. They tied babies' arms and legs down with garish dish towels, leaving only their genitalia exposed and freezing, and they tormented them by waving battery-operated toys in their faces all day.

"Damn! If I could only find those fucking exams!"

Mustapha put his nightmare on hold and stared at him. Polly stared also.

"You lost the exams? What kind of teacher are you?" cried Mustapha. "What did they say?"

"I didn't get a chance to look at them."

Shocked silence from a man whose village was rocketed to toothpicks when he was nine.

"You lost them in this flat somewhere?" asked Polly.

"I assume so."

"Then we will find them," said Mustapha. He glanced into the sleeping alcove at the eight-month-old supply of ungraded post-graduate themes, a baby of similar age with universal solvent saliva making papier mache from the flimsy pages.

"Maybe we'll find them," said Polly.

"No, we must find them," said Mustapha. "The leaders would never want them made known. Most of the cadres are planning trips to America soon to purchase the Three Bigs, and they don't want their exit visas jeopardized by attention paid to political unrest at this university. These are precious annals-of-freedom documents. So I shall translate them and we can post them to The New Republic."

"Now hold on a minute," Sam said. "What if--"

"Or maybe The National Enquirer. They must be posted from the branch office near my university. It's more dependable. Or does your foreign affairs department have guangxi with the clerks there?

Pecks at the door were heard.

Sam said, "I better go jack the dean off some more, before Trigger sends him to fetch the Public Security Bureau."

"No," said Mustapha. "Jacking off time is finished. We will search this place after you have burned something." A glance at Polly brought forth a slight smile.

"Yes, Sammy," she said. "You've got to burn something made of paper."

Polly reached under the bed and produced a complete, unabridged, thirty five-cent Pocket Book Special 1946 edition of Dr. Spock. It was something she had found under a pile of rotting blue stencils in a corner of the so called library. It had evidently been a missionary's copy, inscribed with various religious citations and dedications, perhaps used to rear a child of God who was to be expelled by the Chi-coms Before he/she could learn to forget Daddy's identity at the age of four months, as the doctor predicts in an early chapter. It was the edition where all babies are referred to with the masculine pronoun, and only Daddy works, and the doctor will come to your house the moment the baby's stool liquifies. The cover was hanging loose, but the volume itself was solid. It had survived Liberation, the Anti-Rightist Campaign, the Three Red Flags Movement, the Cultural Revolution, the Struggle to Combat Spiritual Pollution, and it made an admirable bonfire in the bathtub.

"It looks all wrong," said Mustapha. "They'll never believe this is the proper set of ashes." He stirred them with his toe.

Polly said, "Of course, you're aware that they'll tear this place to pieces the minute we all go down to the cafeteria for lunch."

"How about our jade chop?" asked Sam. "We might put strips of paper across the door, glue them into place, seal them in red ink with our jade chop and--"

"Are you willing to perform this ritual every time you step across the threshold?" said Mustapha. "And do you really suppose a few pieces of rice paper would deter these men who took this town away from the Japanese, Chiang Kai Shek and the Americans one-two-three? No, not only must we find the essays, but we must cleanse this flat of very piece of paper in it. Your Chinese friends' lives are forfeit if their names appear anywhere in this room."

Mustapha almost leapt in his glee at the grandeur of his own suggestion. "Yes," he said, "give everything to the xiao har. She'll eat them. But first, you must let the old teacher and the spy into your bathroom and display the ashes to them. Chagrin them. Mention academic freedom and righteousness."

They gathered around to primp Sam up a bit before he fetched the commies in.

"Give those terrible men a moving speech," said Mustapha. "Mention Abraham Lincoln."

"Lu Xun," said Polly.

"Yes, for sure Lu Xun. And Joan of Arc."

"Baba," said the baby through a mouthful of paper. Chinese for Daddy.

Then, almost cackling, Mustapha pushed Sam to the door, unlatched it for him and herded the woman and child to hide in the kitchen.

Rong could be heard whispering something hopeless in Chinese about returning at a more convenient time. Sam opened the door and said, "Careful, Professor. You may get yourself Hu You Banged."

"I beg your pardon?"

"Send the boy away and we'll discuss this seriously."

A plea for pity welled up in his ancient eyes. "I cannot," he said. Obviously he couldn't discuss the nature of his relationship with Trigger, so he started in on his spiel again, from the top.

Sam had listened to this on occasions as innocuous as dinner invitations. But this time, though the words were verbatim, the delivery was different--pure terror, like an animal's. More was at stake here than just his apartment on the fifth floor where the rats were a little less dense. Rong knew first-hand what "the leaders" were capable of. The adolescent fury of the Red Guards had merely been a surgical instrument in their hands.

Sam had to look away.

He saw Trigger now. Distinguished only by an extra-tough pair of buttocks, able to withstand extra hours of hard-bench political study meetings, this boy exerted the power of terror over a venerated scholar. Sam was frightened by totalitarian instincts in such a young man. What would he be like when the cynicism of middle age set in, if he was already "betraying to the authorities"? Prepare a post in Beijing; someone is on his way.

"Welcome, Trigger," said Sam. "I have something to warm you up. Won't you come peek in my bathtub? Notice the label on the porcelain: Victory Brand. Does that ring a bell in a postgraduate's little brain? It should. Answer carefully now."

"You have burned nothing," said Trigger. "The papers are concealed somewhere." He spoke in Chinese. This informant planted among the English majors couldn't cough up enough English to express such a complex notion.

"What kind of fucking grade do you expect to get off me?" Sam screamed down into his face. "How about I give you a makeup exam right now? Define crimethink. Identify Big Brother. You little puke, I--"

Something exploded like gunpowder in Trigger's eyes. Though his body kept still, his mouth silent, Trigger's eyes spoke to Sam, and they said, "I know you social-climbing aesthetes. China had plenty of you before Liberation. All I have to do is write two consecutive, parsable sentences and you'll give me at least a B-plus. These ashes mean nothing to you, San Mu Lao Shi. You gorge yourself on Chinese rice, and you puff up your vita with Chinese publications to bring the personal fame which the declining bourgeoisie crave as a substitute for the self-respect that capitalism fails to provide. You assume that soon you'll return to your country and lay your head down in peace. But we have to stay here and try to keep from smothering each other. This is your forty days in the wilderness. For us it's been forty centuries."

"The leaders will consider this an unfriendly act," said Rong. He somehow managed to storm out of the flat while simultaneously asking Trigger's permission to do so.

Trigger removed his eyes from Sam and quietly followed the old man out the door.

"What does the baby have in her mouth?"

"What doesn't she have in her mouth?"

"It looks as though she has found the papers."

Sam's daughter was on the kitchen floor, selecting mushy fragments from her behind-the-fridge stash of subversive documents and doling them out to Sam's wife and pal, who squatted in an adoring semicircle before her.

Polly gave Sam a couple of handfuls and said, "Those students trusted you with their words. You have honor."

It was the first time that possibility had occurred to him.

They all sat down to read the curiously tight, controlled hands:

We are finished with the ten years' chaos. We are modernizing now, and the people don't need to hear bad news....

The workers are not involved and the students are nothing without them. So foreign experts need not write home saying that our society is unstable....

A foreigner, especially an American, can never understand what Lu Xun meant when he said, "In China, men eat each other." If we take a look at the way men are behaving today in the new free markets, we will see why we must move more slowly, why we are still unfit for democracy....

The younger students are just bored. They think that democracy is disco dancing and brawls in the lunch lines. This is nothing....

Mustapha lay down on the bamboo mats to sleep, cursing under his breath. Polly fixed instant noodles.

Sam and the baby made lots of spitballs.